- Home

- Katherine Davey

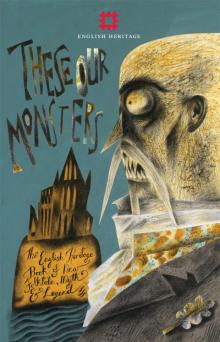

These Our Monsters Page 4

These Our Monsters Read online

Page 4

The priest he cautions against that.

If we feed them we wonder do we give them people food or animal food. Fit for a person? Fit for a pig?

This is a philosophical statement, Priest says, and he wonders which is the right way. He comes down on the people side and so we get.

Bread, they won’t touch it. Though it is such good bread. Old maybe but no one told them that. Good bread it is. Eat up, eat! They do not.

Chicken, little bit. Go on then, eat, eat. They do not. Our wrong children. Right good chicken. How we scrape the floor with our feet at that and shake our fists at them.

Pig then, you pigs eat pig have pig little ham piece piggy piggy but not much. Go on. It’s good then, but no. Too good we think. And yet they won’t. DO. NOT. TO. OUR. GOOD. PIGMEAT. They make us fury mad.

Turnip?

No!

Beetroot?

No, they don’t. Nothing.

What shall we? Such fuss. We kick them then so they know we’re not best pleased. And the boy collapses and is very still for a bit but then in the end he moves again. They wish to starve. So then, thin yourself to death.

But then the green girly she sees the stalks of broad beans we have in a bucket. And she starts crying.

Crying for broad bean stalks and so we give and how the boy and the girl both laugh and cry at that. Only they’ve forgotten how to eat and try the stalks and we show them, show them slow, because they’re so stupid and understand nothing of anything. We teach them broad beans. For we know the broad bean, we are familiar with one another. We open them and show the treasure inside. And they look upon us like we’ve worked the miracle.

And then! And then!

How they do eat. Broad bean follows broad bean deep down into their inner greenlands. And this is all they feel like. Breakfast is broad beans. Lunch broad beans is. They sup upon the broad bean at the end of the day.

Well we say, they are green, makes sense perhaps.

We go off the broad bean ourselves a little from that day.

Then, the next verse of our history, the lord do come. Such is the fame of our green ones. Not the Lord, we’re not that famous, but only local famous. The local lord, Sir Richard de Calne himself. The knight, the holder of land. He has heard of our goblins two. He wishes to see.

They came to us, we say, the green ones did. They are ourn, we say. And we stand before the shed, all of us as a wall.

Let me in, he says.

They are foul, we.

Let me in, he.

Small and ugly.

Let me in.

And most of all green green.

In I do command.

And so we pull back the latch. Again the smell comes into our noses.

And so this baronet comes in and looks about. And so there are knighted eyes upon them.

He has a home as big as all of ours put together and with others added too on top of that. Big as churches. But not as big as the Abbey of Bury Saint Edmonds. And lands. Such property and now to add to all this parkland and cows and sheep and pigs and silver most likely lots of we think and now he wants the green ones too. That man he wants a lot. Our green, we say.

My green, he say. You are starving them.

Ours to starve.

For their protection I shall take them.

We fed them. Beans is all they eat. Broad beans, we say. They eat our broad beans, the green devils.

The boy, he says, is most miserable. He is starving.

No, we say, broad beans. We fed them up.

They are dying.

He takes them. Both. Even though the girl is not so boney. Still he’ll have the lot.

We shall have more broad beans to us now.

And so we have a change again and see them less. The green people are taken away and we say, good thank you we never liked them you have them then. Not ours, never were. God bye. We find we miss them. The days drag greenless.

But. And yet. Wait a little. Though they are no longer in our village, still we think on them. And we do wonder over them. The wondering, you see, comes back thick and fast. We wait for more green folk. But they come not. We think about the green children. Who are they indeed? And what? And where do they come from? Tis most strange that they should come to us, no? There must be a reason for it. To come to us, to Woolpit. We want to know what sort of monsters are they, our monsters? What type is that? But Sir R. he keeps them in his great house. And yet we are not all shut out. Some of us do work for Sir R. in his kitchens and dairies, in his stables and smokehouses. And so we get news of our green folk.

They have school!

Goblin school?

And they learn. To speak like they were Suffolk born.

They learn more and more and are become knowledgeable goblins both. Only one of them, the male one, the boy, the younger – it must be the schooling we think – is not doing well. Is mostly in his bed. He has a bed? No wonder then he’s failing.

Weeks and months and seasons and no one tells us anything particularly green.

But then the boy is more unwell. But then the boy is most unwell. And then we hear that the boy has died. We blame them. Sir Richard the boy killer. Was living when we had him. Should have stayed with us. To kill a goblin boy like that! He was bony like a fish. More bones than us we think. What a thing to die so far from home. Perhaps, we wonder, they stopped giving out the broad beans.

And then when we think the story is done, a whole two years after, we see her again, the green girl. She’s grown older. A woman now. Plump. Ripe. Look there, her skin. What? Not green, is it. What? No, not no more. Pink like us. Is not right, is wrong to lie so. To let your skin tell such tales. Like she was one of us. But we know, we know. And listen, she talk. She always did, grunt and groan, whoops and whistle, squeals and screams. When we poked her. No no, listen, her talks come different.

How so? She talk like us.

She talks.

And we understand.

Is devil, isn’t it?

She talks.

Like as one of us.

Tell us then, at last. Tell us truth, if you may. We’ve been waiting. We deserve to know. We found you after all, we fed you. Shelter we have given. Tell then, do tell.

And, harken, she speaks now. We have such questions. The truth is coming up, from out of her mouth. Words, words.

I cannot tell you where my old home is exactly, says she, only that it is somewhere under the ground. In the ground, deep down. The sun does not rise upon our countrymen; our land is little cheered by its beams; we are contented with that twilight, which, among you, precedes the sun-rise, or follows the sunset. Moreover, a certain luminous country is seen, not far distant from ours, and divided from it by a very considerable river. Nor can I say how we happened to come so lost. We only remember this, that on a certain day, when we were feeding our father’s flocks in the fields, we heard a great sound, such as we are now accustomed to hear at Saint Edmund’s, when the bells are chiming; and whilst listening to the sound in admiration, we became on a sudden, as it were, entranced, and found ourselves among you in the fields where you were reaping. We never could find our home again afterwards.

So now I am here. What my name was before I cannot remember. And I can no longer ask my brother who you starved. But now I have been given a new name. Yes, indeed. I have a name.

We wait, we wait for the name. Shall it be Samaela or Beliala? Or perhaps Lilith or Batibat? Beelzebee, we suggest, Samalla? Mephistofola, is that it?

Agnes, she says, I am called.

You are green and goblin.

I am Agnes, and I live up at the big house.

You were green once, we know. We know we know.

I am Agnes.

We found you.

I am going to marry Sir Richard.

No! He’d never. Such foreign flesh.

It shall be. I am Lady Agnes. If ever you see me after you must bow.

We know you.

Or be whipped.

We

do then close in one around the other of us and is our turn to mutter mutter. There is another world we say, another world deep beneath us. Fancy. Why then does she smile so.

Agnes, she says once more in case we’d forgot. And she goes. And she never comes again. Not to Woolpit. Other people have her now. She’s not ours no more. To take such a woman to your bed! We spit at that and spit and spit and till the taste of the broad bean is in our mouths. We had her when she was green, we had her then. Never Agnes to us. How could she be an Agnes. And we wonder sometimes, if she still favours the broad bean.

How she did eat them. Like a little monster.

Great

Pucklands

Alison MacLeod

IN THE HONEYED LIGHT of late afternoon, they climb, nanometre by nanometre, from the blooms of Great Pucklands, to flutter on the last of the day’s thermals. In the meadow, the air vibrates with the beating of countless wings. Izz, izz, izzzzzz.

The fairies’ ring is marked by tall, dark grass too sour to tempt any cow. As the bugle flowers blow, they descend. The dance begins. They dip and leap. They link and unlink arms in reels, sequences and flights – over and under, in and out, whirr and whoosh.

Poppy-dust streams. Fairy hair rises, crackling with static. Izzz, izzz, izzz. The air is a frenzy of wings.

The bellflowers ring out. Foxgloves tower and teeter. Fairies couple and uncouple, their bodies sticky with pollen. Wild orchids open to long-tongued bees.

At the tangled edge, where bright meadow meets dark wood, hunchbacked fairies stitch the fabric of life. Their needles are stingers ripped from living wasps. Their thread is yanked from the cocoons of mulberry trees. A single strand of cocoon silk is a thousand feet long; they unwind each chrysalis to a certain death. Spin, spin, spin.

Bent over their work, they cut, splice and sew with algorithmic speed. Chromosomes split, fray and are re-stitched. Genes switch on. Seedpods burst. Saplings spring forth. Bindweed chokes buttercups. A curlew is hatched. Foetuses unfold as tenderly as new ferns; others wither in the womb. Life fizzles and fizzes onward. Izzz, izzz, izz, izz.

That summer, the sound of bees in the village of Down was quite extraordinary. On the chalky escarpment, high above Cudham Valley in the North Downs, a loud buzzing arose from Great Pucklands. Only Anne Elizabeth Darwin – Annie – aged nine, and her father understood that the sound was too loud for bees alone.

He emerged from the village shop, gripping castor wheels for his microscope-stool. ‘Spied any yet?’

She shook her head. ‘But I hear them. Have you, Papa? Seen any?’

He said he wasn’t sure he wanted to see them. Fairies weren’t always pretty mites. That was just tales people told for babies.

‘But you do have your beetle jar,’ she said, ‘in case we see one?’

He patted his jacket pocket reassuringly, then passed her a liquorice string. She jumped joyfully, calling to mind a rhinoceros he’d once seen in the Zoological Gardens in London. Its keeper had let it out of its pen into the sunshine, and the rhino had kicked and bucked with irrefutable joy.

We are all netted together, he thought.

‘We might see one on the way home,’ Annie ventured.

‘A beetle or a fairy?’

‘Both, perhaps!’

At St Mary’s lych-gate, she turned a cartwheel, and her locket slipped from her chest and knocked her forehead. She righted herself and grinned.

Alfred Greenleaf, the old carpenter, passed at that moment, tipping his hat. ‘Afternoon, Mr Darwin.’ Alfred had what looked like a tree-burr growing from his cheek, and Annie stared, delighted, until her father hauled her on.

***

At Down House, she ran up the stairs to the nursery and leaped over the deep dip in the boards at the top, the warp which the children knew as ‘The Bottomless Hole’. No matter how fast they ran, they knew to step over or around The Bottomless Hole and never into it – lest they go down, down, down, forever.

She arrived, sweaty, at her desk and entered her Equation of Ancestry in the paper book she had made and stitched herself: ‘Conifers – woody flowering plants – Oak Trees – Alfred Greenleaf.’ She made each of her letters carefully, adding curls to her capitals.

Her father was teaching her about lines of inheritance. Sometimes, when she was poorly or tired, she was allowed to rest on the couch in his study while he did his barnacles. Then he would take down from his shelf The Zoology of South Africa and let her turn its pages. She loved the drawings of the primitive hominins and monkeys best.

She paused at her inkpot long enough to allow Brodie, her nurse, to scrub the liquorice from her face. Then she added another Equation she’d devised: ‘Larva – Pupa – Slug – Winged Insect – Winged Fairy – Hominin – Human.’ Fairies and people shared a line of inheritance. Her Equation proved it.

Annie had three things of her own: a locket, given to her by her mother, which waited for something to close inside and wear by her heart; a beautiful barnacle shell from New South Wales, given to her by her father; and a new wooden writing-box, given to her by her parents for her ninth birthday.

The writing-box was covered in morocco leather. It was a smaller version of her mother’s writing-box, with a hinged lid and compartments inside lined with crimson paper and gold stars.

Having completed her newest Equation, she closed her jotting-book and locked it inside her writing-box. Then she took the writing-box’s tiny key and closed it in her locket.

That night, with her head on the bolster she shared with her little sister Etty, she asked her father which genus of tree Alfred Greenleaf shared an ancestor with.

‘Which would you say?’

‘Oak. Or possibly Copper Beech.’

He laughed and thumped his leg, a sign, Annie told herself, of his pleasure in her Equation. Then he explained that her locket was for daytime only. He unfastened it gently where it was caught in her hair and kissed her goodnight. Cracks of light from the shutters made it hard to close her eyes. She stared at her barnacle shell, and then it was morning again.

At Down House that June, there wasn’t a breath of air. The grass was burnt brown. Great cracks had opened in the ground. Between the two old yew trees, the swing hardly moved.

Brodie, Miss Thorley, the governess, and her mother carried fans wherever they went. Their fans, when opened, were as splendid, Annie thought, as the wings of bats.

She knew because one evening, a few weeks before, her father had laid out his specimen trays for her on the floor of the nursery. Bones were pinned into place on sheets of cork. The bat’s wing, he told her, was related to the porpoise’s fin and the horse’s leg, and all three were related to the human hand. ‘Can you see?’ he asked.

She fingered the bones and nodded. Then she ran to the nursery desk where she wrote her very first Equation in her paper book: ‘Bat – Porpoise – Horse – Human.’

Her father nabbed her nose. ‘Not a word to your ever-loving Mama.’

‘About bat wings and hands?’

‘About bat wings and hands.’

Neither of them wanted to make her cry.

Her mother had explained to her that God made all the animals on the Sixth Day of Creation. She’d explained that, when the Flood came, Noah saved the animals, taking them into the Ark two by two, which was why they were still with us today, just as God had made them. She’d smiled and walked the four fingers of both hands along Annie’s legs.

Her mother re-told the story when Etty and George were old enough to sit still. ‘Did Noah take the intermediate species too?’ Annie asked at the end.

Her mother looked at her hands. Her forehead crinkled. She said little girls and boys needed only to love and delight in the Word of God, and she cut out paper animals for them, two at a time. She made excellent bears and lions, but pigs, they all agreed that day, were her masterpieces.

It was midsummer 1850, the bright beautiful hinge of the summer and the century – and another scorcher of a day. Croquet mallets, h

oops and tennis racquets lay strewn across the lawn, like mismatched skeleton parts. Three of the children stretched out as well, sweaty and sunburnt on the grass, with starfish arms and legs. Willy was not yet home for summer from Mr Wharton’s School, and Betty and Francis were too little to play out in the sun.

Faces to the sky, Annie, Etty and George sucked nectar from the sage flowers they’d stolen from the kitchen garden. For a time, they listened to Parslow, their father’s man, draw water from the well in the service yard. Skr-eeee, skr-eeee went the fly-wheel.

Their mother, Miss Thorley and Brodie picked up their cane chairs and moved them away from the noise, into the shade of the Horse Chestnut. Their mother was beautiful in her lilac muslin. They watched her shoo a bee and pour the tea.

Ladies weren’t allowed to make a pot of tea, Annie explained to Etty and George, unless they were Mrs Davies the cook. Ladies couldn’t post a letter or ride in a train carriage by themselves. Nor could they go out in the dark alone to watch for owls, badgers or shooting stars. That’s why she was never going to be a lady. Her mind was made up.

Etty said she might become a lady if she didn’t have to ride a pony side-saddle. Annie said she never would. George said he never would either, and, in solidarity, laid his small head in Annie’s lap.

Skr-eeee, skr-eeee. Poor Parslow. The flowers were wilting in every bed, their father was poorly and needed buckets and bucketsful every day for his water-therapy, and there was never water enough for the house. Mrs Davies shouted and the maids simmered in the heat.

On Mrs Davies’ stove, a vole also simmered, making the kitchen smell foul, which did not improve Mrs Davies’ temper. Later, Annie and her father would strip it down to its skeleton and pin it out.

That summer, her father’s Great Secret also simmered. His special Equation. His Origin. The one he scribbled when her mother thought he was doing his barnacles; the one that gave him palpitations and cold, sweaty skin. He wrote it down on scraps of paper and hid them in his table drawer, in his coat pockets and under specimen jars, as if he were hiding them from even himself.

The wide Kent sky was a lid on the pot of Down House that summer. Bubble, bubble.

These Our Monsters

These Our Monsters